In this edition of Meet the Makers, we chat with multidisciplinary artist Przemek Branas, whose practice spans performance, video, and installation. With a deep interest in exploring social contexts and how stories are told, Przemek’s art often blurs the boundaries between the past and present, offering thought-provoking insights into contemporary life.

In this conversation, Przemek reflects on his dual identity as both an artisan and researcher, a combination that fuels his dynamic creative process. We also delve into the themes of his upcoming exhibition in Barcelona, where the mythical figure of the uroboros, a snake eating its own tail, takes center stage. Through this symbolic motif, Przemek explores cycles of creation and decay, offering viewers an intricate, layered experience that leaves much to interpretation. Get ready to dive into a world where art blurs boundaries, questions conventions, and sparks curiosity.

1. You’re originally from Jarosław, Poland, but now you’re based in Portugal. How have these different environments influenced your artistic practice?

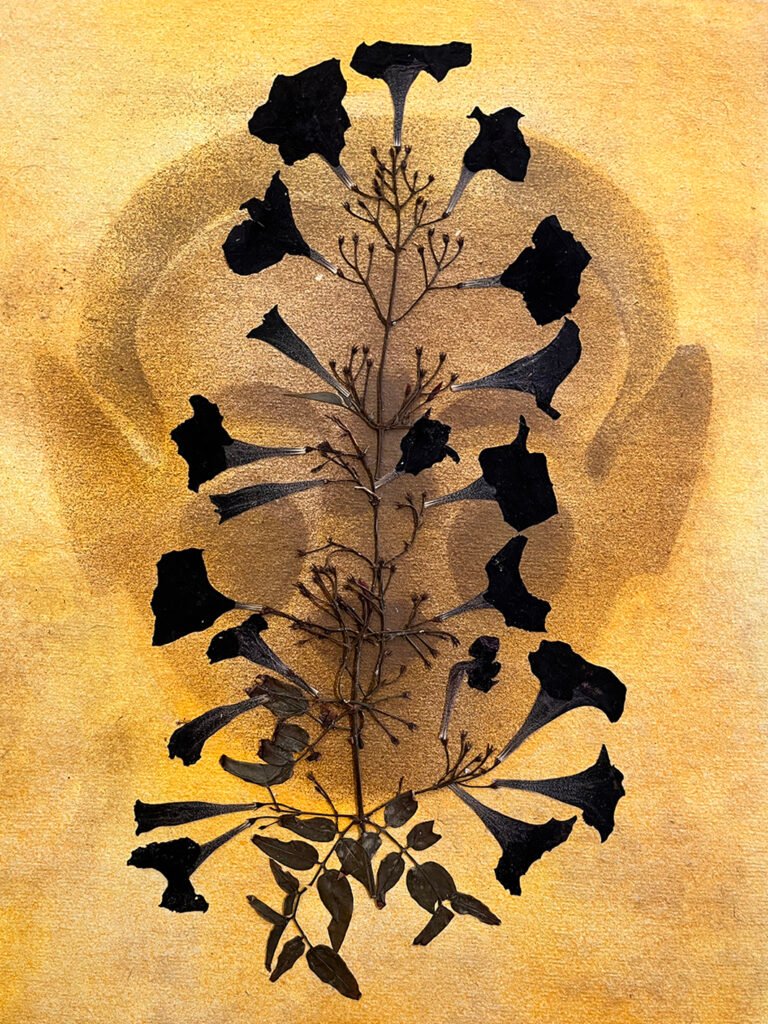

Every environment I have been in and lived in has influenced me and my artistic practice. Different ideas and concepts are inspired by the place in which they are created. I work closely with physical matter, which often comes from the location where the work is made. On the Portuguese coast, I began working on a series of new collages entitled ‘Weeds, Beasts, Queers’, which I created using plant species found on site. I catalog them, describe them, classify them, and dry them in a botanical press. I consider this activity a performative part of my artistic practice.

2. You describe yourself as an artisan and a researcher. How does this dual identity influence your artistic practice?

It’s natural for me to work across research, craft, and the creation of aesthetic works. It’s a multi-disciplinary practice that draws from various established fields. This kind of fusion and mixing gives me a sense of using my own language, of creating a kind of grotesque in my expressive process.

3. Your work often explores social contexts and aims to irritate and reveal. How do you choose which social issues to focus on, and what role do you see art playing in these discussions?

Nowadays, I work with phenomena, situations, and themes that touch on human experiences but are more abstract and difficult to define. In the past, I have worked on identity and gender issues, but I have also often explored historical events that I believe had a significant impact on reality, yet are now overlooked. I remain interested in figures from the past—their lives, biographies, and artistic practices. I particularly enjoy engaging with these historical layers.

For example, in the work ‘I Wanna Be Your Colonizer’, I created a series of performance actions based on photographs from the 1930s depicting a man in the Caribbean. I impersonated, queered, and colonized his image. Perhaps this is because reality itself often seems vague to me—a mixture of straightforward messages and blurry, complex images. Similarly, Timothée Morton’s ‘Dark Ecology, which we reference in the exhibition at CasCaDas ArtSpace, deals with subjects that often seem disconnected. Only over time, with perspective, do I begin to see the bigger picture—the connections and the weave that binds them together.

4. You work across various media like performance, video, and installation. What do you enjoy most about blending these forms, and how do they interact in your exhibitions?

Firstly, I enjoy working on something that feels new and fresh. I like to learn, and often I focus that learning solely on a given project. Working with different media—from performance to installation to photography—gives me a sense of building a more complete picture, much like reality. This approach may make it more difficult for the viewer, as messages and information can become blurred or duplicated, but it reflects how I perceive reality.

A good example of this would be the ‘Moonrise’ project, where I began my performative engagement with nature, flowers, and plants in 2017 during a fellowship and residency in Giverny, France (Terra Foundation for American Art). This practice, and learning to work with plants, allowed me to return to working with them in the future—which happens to be now. A kind of herbarium was created during that time, with specimens collected from the Claude Monet Gardens in Giverny. As part of this process, I also created a poison, distilled from the toxic parts of various plants.

5. Storytelling plays a significant role in your art, but you’re particularly interested in how stories are constructed. Could you share more about what fascinates you in the ‘invisible joints’ and ‘cracks’ of a narrative?

The cracks in the narrative suggest that something more is hidden beneath the surface. It’s this rupture that allows us to look deeper or open ourselves to new perspectives. Narrating through my works, on the other hand, gives me the sense that a subject or piece is never truly a closed form. The context of place, or even time, along with the various events that occur, allows stories to be re-told and re-explored.

I am particularly drawn to the casket structure of storytelling: inside one casket is another, smaller one, and inside that is an even smaller one, continuing on and on. Perhaps the smallest one holds the crux of the matter—or perhaps it doesn’t.

6. Your practice treads a line between core and periphery, voyeurism and motion. How do these themes manifest in your upcoming exhibition in Barcelona?

Together with curator Michalina Sablik, we decided to present a simple yet intricate story based on the transcultural mythical motif of the Uroboros—a snake eating its own tail. If there is a figure that can embody oscillation between the center (core) and the periphery, as well as being both trickster and serious, it is the Uroboros.

7. In a world where political rebellion often feels exhausted, you believe artists should ‘pick on the social body.’ How do you see your role as an artist in this context?

I believe artists should follow their instincts and do what they feel compelled to do. My work addresses issues central to today’s political debates, such as identity, visions of the future, our relationship with nature, and the interpretation of cultural heritage and history, but it never tells these stories directly.

8. The Man Eating His Own Tail” is such an evocative title. Can you tell us more about the inspiration behind it and how it relates to the concept of the uroboros. What conversations or reflections do you hope to spark?

The title of the work is playful and stimulates the imagination. It is an open-ended form of expression that doesn’t provide the viewer with a clear message but instead activates their intellect and creativity. ‘Man Eats His Own Tail’ is the centerpiece installation in the exhibition: a large, multi-part object, with a key element being a replica of the mask seen in the exhibition’s photographs—except this one has an open mouth. The mask in the photographs appears twice: it is a disposable mask made of lemon peels, which I wore during a kind of performative play on the beach, documented through photography. The mask was disposable because, after use, it began to mold and decay. Natural decomposition processes set in, but much faster than they would on the human face. I interpreted this as an accelerated aging process. While the mask was ephemeral, the cast in the sculpture preserves its form, revealing what it truly looked like.

The entire sculpture is made of paper pulp, which I create from scratch. It imitates stone or some heavy, gray, indefinable matter. The work tells a story of looping—looping in, creating narratives, relationships, and connections. On a theoretical or philosophical level, we draw from Timothy Morton’s ‘Dark Ecology’. In his book, the uroboros appears on many levels—both on a meta-level and in the practical moments of everyday life.

On a meta-level, my work reflects both the individual (the human being) and the collective (the community). In the exhibition, the installation blends a snake and a man wearing a mask made from fruit. This grotesque combination is, for me, a commentary on reality—how I perceive, define, and, perhaps, queer it. The uroboros is a symbol that appears across many cultures, laden with strong symbolism and an intriguing history. The exhibition presents a work that feels like a space for reflection, as it offers no clear answer as to what—or who—the titular ‘man eating his own tail’ truly is.

Thank you for sharing with us today Przemek! We enjoyed the opening of your show and we’re excited to follow your artistic journey.

For more information about Przemek Branas, visit www.przemekbranas.com and @przemekbranas.

You can visit ‘Man Eating his Own Tail‘ at Cascadas Art Space until November 2nd.

Thanks for your interest in art & creativity on FrikiFish— a one-woman labor of love, providing free content and services to artists, art-lovers and creative projects in-and-around Barcelona. This project runs on caffeine and community love, please consider supporting with a donation or a cup of coffee. Thank you!