Mari Chordà… And many Other Things

Image, language and social action are the foundations of the work of Mari Chordà and an integral part of her life: the artist, the writer and poet, and the activist form an unbreakable bond and a basis for an attitude and convictions that make up the backbone of her work and biography. As well as being an active, attentive observer of the reality around her, she takes part in it, shaking up and subverting everything she sees, guided by a political stance that emerged as a response to the Francoist dictatorship and endured in the form of feminist struggles for the visibility and recognition of women’s work.

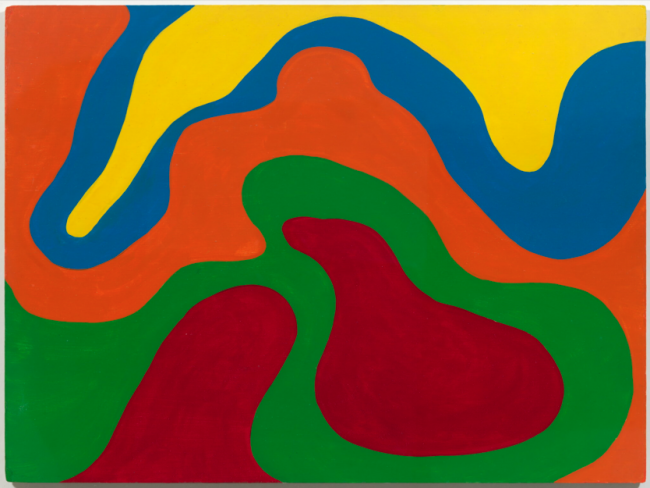

The aesthetic references in Mari Chordà’s work are completely alien both to the academicist, anachronistic environment of the School of Fine Arts where she studied and to the art scene at the time when she started to form her own language. Her imaginary is close to the visual sensitivity of pop art and psychedelia, but she has never considered herself a pop artist. A pioneer in her generation in terms of discussing sexual freedom, she talks about pleasure, motherhood and lesbian relationships in her paintings and poetry.

She painted her first Vagina in 1964, while she was still a student: ‘I imagined the female body on the inside, but it was an unrealistic kind of figurative art, with some recollection of its shapes.’ She paints bodily fluids, secretions, sex organs and sex, not from a perspective of debasement, but with sensual shapes and seductive colours, in solid tones that call for a full, complete kind of eroticism. These are artworks that give off strength and vitality, in which creation is linked to sexual identity: ‘I wanted to “paint-talk” about sexual life and sexual identity.’

Mari Chordà investigates women’s bodies through her own, but instead of portraying her face – as we expect from conventional self-portraits – she explores and depicts herself by painting her genitals. Self-referentiality, the exploration of one’s own intimacy and the changes that take place during pregnancy are just some of the themes examined. There is no obscenity or shame of any kind when it comes to showing or talking about sex, to enjoying the body and painting it or writing poems about it. While the State, the Church, the establishment or a misunderstood morality encouraged the repression of sex and pleasure, the exacerbated sexuality in Chordà’s work represents self-affirmation and legitimises freedom and joy.

Like other women of her generation, Mari Chordà believed that ‘the personal was political’3 and made this conviction a driving force in her life. She founded Lo Llar in Amposta: a hive of cultural activity that hosted concerts, exhibitions and endless other events. After moving to Barcelona, she and a group of other women created laSal, a collectively organised bar-library intended as a meeting place for women to talk and support each other, which gave rise to ‘laSal, edicions de les dones’, the first feminist publishing house in Spain specialising in women’s literature and essays. But laSal was also a place for having fun: ‘We devoted ourselves to generating words, generating music and, especially, generating pleasure … Pleasure is very subversive.’4 Indeed, everything Mari Chordà does is imbued with the need to enjoy and to play, understood as a key part of the fight for women’s rights.